Waking up to Wadjemup

This month, we feature a corporation that has laboured for 25 years for Australians to recognise and properly commemorate the agonising Aboriginal history of Wadjemup, aka Rottnest Island.

WARNING:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: please be aware that the following story contains images of unidentified people who are now deceased.

Wadjemup, Western Australia: Rottnest Island Deaths Group Aboriginal Corporation (RIDGAC) formed in 1993 with a powerful purpose. Its members planned to protect and preserve the burial grounds and spirits of their ancestors. To that end it compiles and shares the devastating history of Aboriginal imprisonment on the island. The corporation has opened and sustained the debate on how we should treat the unidentified bodies of the Wadjemup prisoners and remember their experience. The last day of May 2018 is a major milestone for RIDGAC and all Western Australian Aboriginal people, but there’s a way to go before its duty to the ancestors is done.

Contrasting perspectives

The cultural significance of Rottnest Island varies dramatically depending on your perspective and era. Noongar people call it Wadjemup, meaning place of spirits. It’s a sacred place where forever, ancestral spirits dwell. But Wadjemup is also where, from 1838 to 1904, as colonists settled further and further north from Perth, thousands of Aboriginal men from all over Western Australia were taken, in chains, to be incarcerated in terrible conditions—and where hundreds died and remain buried in unmarked shallow graves.

Nine Aboriginal prisoners (outside Roebourne jail) with neck collars and heavy chains, guarded by three armed white men. State Library of Western Australia BA1713/2

As if that contrast was not enough, from 1907, three years after the prison closed, the island was promoted to non-Indigenous Australians as a tourist destination—and today, it’s a cherished place for recreation. Can those contrasting associations peacefully co-exist? How can those who suffered and died be properly commemorated on an island that half a million tourists visit each year?

Deaths in custody

When it formed 25 years ago, RIDGAC’s first goal was to halt all development on the burial ground, and to lobby for removal of the roads, buildings and campground that were just four feet above the human remains. But exactly where all the graves are remains unclear. Results of the ground-penetrating radar—used to identify disturbance in the earth that is consistent with grave sites, rather than bones themselves—were inconclusive. The alternative—digging up the graves—is also untenable.

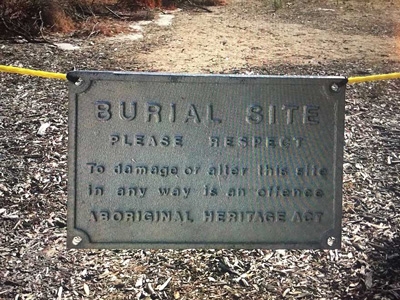

Signage at the burial ground previously acknowledged that the extent of the cemetery is unknown

In 1994 RIDGAC orchestrated a meeting of Aboriginal people from all over Western Australia. Two or three hundred people travelled to the island to take part in a ceremony to rebury the bones of the prisoner that had been accidentally dug up—including senior elders from Noongar country as well as the Goldfields, Western Desert, Pilbara and the Kimberley. Premier Richard Court also attended, and by all accounts it was a powerful meeting. The premier publicly acknowledged Rottnest as Australia’s biggest deaths-in-custody site, and RIDGAC presented him with its proposal for the future of Wadjemup.

Twenty-two years later WA lottery funding was secured for part of a project to restore the area known for certain to be a burial ground. Rottnest Island Authority (RIA), the statutory body established to look after the island, intends to create a respectful, contemplative public space there. But for RIDGAC, the works that have been carried out on that site, and the further proposed works, are premature and contentious. The corporation has consistently urged successive governments and RIA to conduct further exploration to identify additional burial sites, before any further development takes place. And last month historians found a map that identifies cemeteries not previously known to RIA. Without question, there are unmarked graves beyond the bounds of the known burial ground.

Surveyor’s map, c1908, showing the location of two cemeteries separate from the main Aboriginal prisoners’ burial grounds

Penal servitude

The second strategic goal for RIDGAC was to raise awareness of what those Aboriginal prisoners and their communities experienced. In this, their work is focused on the prison building known as the Quod.

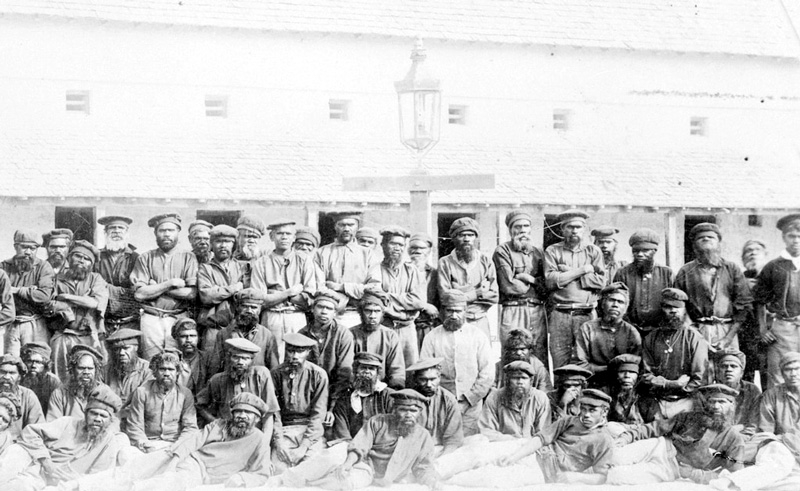

Group of prisoners arranged for a photograph in The Quod, 1893. State Library of Western Australia 5478B/20. (For many years prior, the prisoners had no warm clothing; only a thin blanket.)

The Quod was a panopticon-style prison of small cells (3 x 1.7m), each of which held up to seven people with no windows, no beds, no bucket for a toilet. The people it would incarcerate were forced to build it in 1863, and it was a hellish prison for thousands of men—and boys as young as eight. Disease was rampant, and the longstanding superintendent, Henry Vincent, is notorious for his cruelty.

The floor plan for The Quod in its original form, annotated by Michael Sinclair-Jones.

The Quod's refurbishment as holiday units did not erase all signs of the former prison

Of the 3700 men and boys incarcerated at Wadjemup, an estimated 364 died there. Most others never returned to their home communities. The prison allegedly closed in 1904 but prisoners continued to languish and labour there until 1931.

From 1911, walls between some of the cells were removed to form larger units. Since the 1930s the prison cells have accommodated holiday-makers insensitive to the gruesome history of their sleeping quarters. To this day, Quod rooms are rented as part of a commercial hotel venture.

On 31 May 2018, the last commercial lease for The Quod expires; tourists will sleep there no more. Rottnest Island Deaths Group Aboriginal Corporation sees the handback of The Quod to the Rottnest Island Authority as a long-overdue opportunity to enact plans to properly honour and commemorate the men who died, and to enable visitors to gain a broader and deeper understanding of the significance of the site.

The corporation also remains adamant that the story of Wadjemup should be told from an Aboriginal perspective, in an Aboriginal way. It stands by an earlier press statement (written by former chair of the corporation, Albert Corunna), which states:

Rottnest Island is a death island of Aboriginal people sentenced there, many to die through sickness, coldness, hunger, harsh work, beatings, neglect and most of all, being away from their family structure on the mainland. The Spirit People are still there, the sufferers of Rottnest Island.

The whole of the Quod where they were imprisoned, suffered and many died has to be handed back to their relations, the Aboriginal elders state-wide.

Before Wadjemup was commandeered as a prison, Aboriginal men, boys, women and girls were incarcerated—and some executed—at the Round House in Fremantle, which was the first public building in Western Australia. Like the Quod, it was built in the style of the 'panopticon', which was designed to instil in its occupants a sense of being under surveillance at all times—to mentally enslave them.

A story of Australia

For RIDGAC and many others who know what happened, the systematic dislocation of Aboriginal people and communities was essential to the northward progress of the Western Australian colonial frontier. Chair of the corporation’s board of directors, Iva Hayward-Jackson, says:

The story of the prison at Wadjemup is not just a local story. Aboriginal men were brought here from all over the state. Many were taken for killing cattle—food for their families. They were chained at the neck, wrists and ankles. And they were crammed into small, cold, cells. All of them suffered terribly, and a lot of them died. For those men personally it was agony, and for their families and communities, it was devastating. But for the colony of Western Australia, it was useful to have those men removed. Some of them were just boys but many of them were senior law men defending their land and their lives. And as much as it damaged Aboriginal communities, their removal supported colonial expansion.

If the corporation has its way, visitors to Wadjemup will be invited to own all that as part of our shared Australian history. In other words, the island has the potential to become a vital site for reconciliation. But it can’t happen without due process, Mr Hayward-Jackson says:

Reconciliation is about owning history, not being in denial. All Australians but especially people who visit Wadjemup need to wake up to what happened there. That’s the only way they can have a genuine experience of the place. It doesn’t mean you can’t go and have a nice holiday. It means you can have an authentic physical, mental and spiritual encounter with history. That’s what reconciliation is; that’s what we want. But it can’t happen until we settle what should happen there. And that starts with the elders of our mobs getting together, on Wadjemup.

At the time of writing, directors of RIDGAC were out visiting communities from Alice Springs to the Kimberley, talking and listening and planning a return to Wadjemup, for their first big meeting in 24 years.

Glen Cooke, director, on the road with Iva Hayward-Jackson

The future of Wadjemup

This year’s National Reconciliation Week will include the last day the former prison will be available for commercial accommodation. What happens next—and where all the bodies are—remains unclear.

There are signs that RIA has taken the corporation’s views on board. Its cultural landscape management plan includes a detailed, scathing historical account of the prison and its role in Aboriginal dispossession, and agrees that the island is critical to the nation’s history:

Wadjemup has the potential to become one of the most important focal points for reconciliation and healing between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people not just in Western Australia but for Australia as a nation. For this to occur, the pain and shame of the past needs to be acknowledged, and the untold history of the Island needs to be brought into the open in a much more conspicuous and inclusive way.

For 25 years, Rottnest Island Deaths Group Aboriginal Corporation has raised awareness of Aboriginal–Western Australian history, and sustained the conversation about an appropriate commemoration of the prisoners. And now they’re gathering forces for another big meeting at Wadjemup. It’s a good opportunity for us all to listen, so we’ll give chairman Hayward-Jackson the last word:

We’re relieved that the Quod will no longer be tourist accommodation. But we want some assurance that the future of it and the burial ground is Aboriginal community-controlled. It’s not enough for a memorial and interpretive site to exist. To properly honour and respect our ancestors and Aboriginal people today, it needs to be done in an Aboriginal way. It needs to be governed and run by Aboriginal people.

The meeting in September will be senior lawmakers from a lot of Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. We’re the elders in those communities; and those men taken as prisoners were our elders. So we'll be at Wadjemup all together, and let's see what comes of it.