Only Yolŋu make decisions for this land

Having formed in 1992 to manage threats to the land, Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation now also manages ever-increasing waves of marine debris.

Above: Dhimurru rangers Wanga, Eddie, Grace, Hamish, Gatha, Rrawun, Yama and Guru

Nhulunbuy, north-east Arnhem Land, Northern Territory: At the beginning of every board meeting, directors of Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation read its 400-word vision statement aloud. The ritual honours the corporation’s founder, Roy Marika, progenitor of the land rights movement in Australia, and maintains a very clear focus for the corporation.

An Indigenous protected area

Roy’s son Mandaka Marika is Dhimurru’s managing director, leading a team of Yolŋu rangers, facilitators and administrative staff. It’s a big job, to take care of half a million hectares of land and sea country around the Gove peninsula in north-east Arnhem Land. It’s managed as an ‘Indigenous protected area (IPA)’, which means that traditional owners have agreed, with the Commonwealth government, to protect its environmental and cultural values.

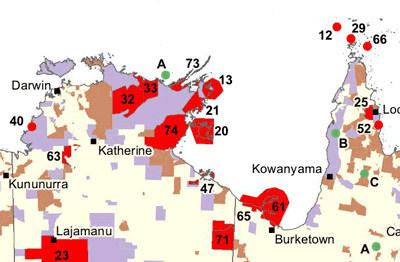

In the map on the left—a detail from the national map on the 'Country needs people' website—Dhimurru is number 13—a polygon with a portion excluded because it’s leased to a mining company. Dedicated in 2000, the Dhimurru IPA was the first in the Northern Territory and the first to include sea country.

Dhimurru itself was established in 1992 after a long gestation period. In the late 1960s, a mining company started building the town of Nhulunbuy (formerly Gove), and many more people started to come to the Gove peninsula from far away. Yolŋu elders were worried about the impact of all those new people on their lands and waters. After extensive consultation, they founded Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation to manage the land and visitors to it. Dhimurru means east wind—the wind that brings the monsoon, rain and new life to the land.

Managing recreational visits

Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation endeavours to provide residents and visitors with an enjoyable recreation experience—and there are many beautiful places there—and at the same time an avenue for enhancing awareness of Yolŋu cultural values. A system of visitor permits controls public access to 20 designated recreation areas and creates a channel of communications between Yolŋu and balanda (non-Indigenous) residents and visitors to:

- alert balanda to hazards such as crocodiles, buffalo, wild pigs and box jellyfish

- encourage balanda to respect access conditions and steer clear of sacred sites.

A holistic approach

True to the vision of Dhimurru’s founders, only Yolŋu make decisions for this land—all decisions about land management activities follow the expressed wishes of the relevant traditional owners. Given the scale of the operation, in some cases that consultation involves working through the Northern Land Council.

A commitment to Yolŋu leadership does not prevent the corporation from engaging with Western knowledge, technologies and techniques. On the contrary (and like other Indigenous ranger groups around the country), Dhimurru has always taken a holistic and collaborative, both-ways approach. The corporation has a kind of motto: Ŋillimurru bukmak djäka waŋuwu, meaning ‘All of us together looking after country’. So for example, Yolŋu use traditional fire techniques but also employ western science and tools to map sea grass (a good measure of a healthy ocean ecosystem) and manage weeds and feral animals.

Its logo beautifully illustrates the corporation’s ethos. Cockatoos are strong characters, friendly and intelligent. One is dhuwa, one yirritja—the two moieties of Yolŋu people. They are circled by a coastal vine that flowers when the winds come from the south-east. So the logo signifies wholeness—cross-clan but also cross-cultural.

Learning on country

The corporation’s Learning on Country program is integral to its operations. From 2013, Dhimurru rangers have worked with Yolŋu children at Yirrkala School to maintain their connection to country and prepare the next generation of Yolŋu land owners to care for their estates. The concept of ‘learning on country’ is also extended to balanda delegates to the annual Garma festival, as Dhimurru rangers join with Yirralka rangers (from Laynhapuy Homelands Aboriginal Corporation) to host walks through a valley on the Gulkula site.

Suring this year's NAIDOC Week, the corporation's bush foods cookup of yams, mud mussels and fish was very popular. Below, paperbark is removed to reveal the cooked yams.

A growing threat

In recent years, the corporation has focused more of its resources on removing ever-increasing waves of marine debris from Wanuwuy that wash in on currents from south-east Asia. In 2018 rangers and volunteers removed, weighed and sorted 2.5 tons of ghost nets, cigarette lighters, bottles, bags and thongs. The corporation’s Sisyphean struggle was documented in stories in the New York Times in October 2018 and Guardian Australia in May 2019.

Taking care of business and country

The corporation is now, as it has always been, at the frontline of systemic threats to country. But Yolŋu people have the resilience and determination to face them and secure their future. Mandaka Marika expresses it this way:

We stand strong here on the Gove peninsula, looking after the sea and the land, trying to stop the pollution and protect the turtles. In the songlines of the turtle you will hear the word gundah or muruwirri or naripal. It means the shell is like a rock. And that’s a metaphor for my people. Our strength lies not in the rock but in ourselves. We need to stay strong for our land. We are the caretakers.

How you can help

If you’re in the Nhulunbuy area, you can join a volunteer crew to help clear the marine debris. Or you could support the rangers through the Dhimurru shop.