Breathing in Mannalargenna

Melythina Tiakana Warrana (Heart of Country) Aboriginal Corporation supports people to understand and reconnect with the culture and history of north-east Tasmania.

Kingston Beach, Tasmania

First, the big picture

The scientific view is that Aboriginal people walked from mainland Australia to Trouwunna/Loetrouwitter (Tasmania) over forty thousand years ago—twenty-eight thousand years before the sea rose to create the island.

Tasmania’s first people believed that they were created by two spirit beings who came from the stars near Orion’s Belt. They travelled across the Milky Way to this island where they built the mountains, cut the rivers with their stone tools and made all living things, including the people, animals and plants, out of the ground.

From the beginning of colonisation, British military personnel, convicts and free colonists regarded Aboriginal people with hostility, and the relationship quickly descended into unjust warfare, with severe consequences for all the Aboriginal clans. In 1803 there were still only a couple of thousand British—mostly military personnel and convicts—living on the island and (according to Henry Melville) up to twenty thousand Aboriginal people. Thirty years later the population of British—including free colonists—had soared to around 23,500, and only a few hundred Aboriginal people remained alive in the bush.

This is a story of survival and resilience under the worst conditions imaginable, and a corporation that supports people to understand history as they reconnect with their ancestral lands and celebrate cultural practices. Melythina Tiakana Warrana (Heart of Country) Aboriginal Corporation is focused on the people of Tebrakunna Country (also known as the Cape Portland area) in north-east Tasmania. It registered in 2008 and on 4 December 2015 it hosted the inaugural—now annual—Mannalargenna Day.

Mannalargenna

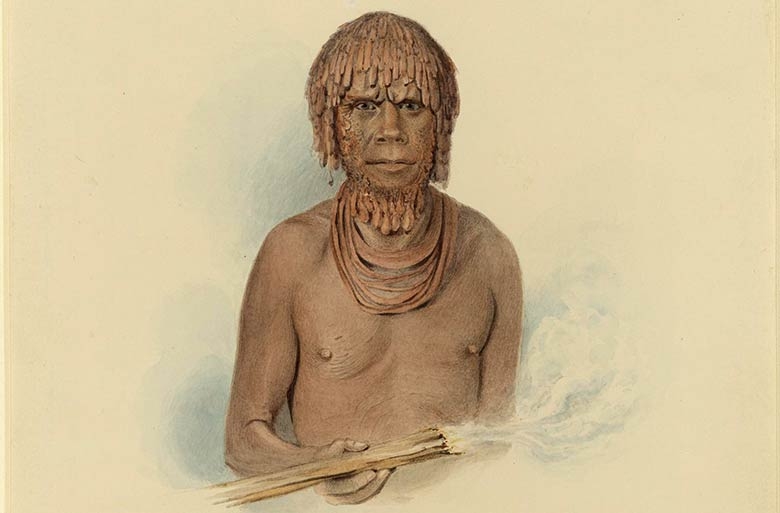

Watercolour drawing of Mannalargenna by convict artist Thomas Bock, held by The British Museum. Mannalargenna’s skin and hair are coated in ochre and he holds a paperbark fire stick.

Mannalargenna was a seer and leader of the Pairrebeenne/Trawlwoolway clan of the Coastal Plains nation, revered for having powers over the wind. He was also a formidable warrior who danced to avoid spears thrown in clan attacks; and a guerilla fighter during the colonial wars. In 1829 he freed four Aboriginal women and a boy from John Batman's house where they had been held captive for a year. As the above drawing shows, he liked to cover his skin and hair in grease and ochre. (This account by Emma Lee, a member of Melythina Tiakana Warrana, explains the importance of ochre.)

In 1830 Mannalargenna met George Augustus Robinson, whom the colony’s governor (George Arthur) had commissioned to persuade the remaining first people to self-exile to the islands off Tasmania. Robinson told Mannalargenna that if he helped persuade the clans to move away from the homelands, it would be temporary. On 6 August 1831 Robinson promised they could one day return to their ancestral lands and live, hunt and practise their culture in safety. The same promise was repeated to three other clan leaders that year: Maulterheerlargenna of the Stoney Creek nation; Tongerlongter of the Oyster Bay nation; and Montpelliater of the Big River nation.

As a powerful leader and negotiator, Mannalargenna agreed to accompany Robinson on his mission. After four years assisting Robinson, in late 1835 Mannalargenna himself moved to the Wybalenna Aboriginal establishment on Flinders Island.

Ultimately, Robinson broke his promise. As a symbol of the betrayal, Mannalargenna cut off his long ochred hair and beard. On 4 December 1835 he died of pneumonia.

It was only after petitioning Queen Victoria in 1846 that the remaining 47 inhabitants of Wybalenna were allowed to return to mainland Trouwunna/Loetrouwitter—but not to their respective homelands. They were moved to a condemned penal station at Oyster Cove, a damp miserable place south of Hobart.

Aboriginal Tasmanians survived in no small part because of the women—such as Mannalargenna’s four daughters—who from 1810 married white straitsmen and made their homes on the small islands of eastern Bass Strait. Out of necessity, their cultural practices adapted, but they continued to pass on their cultural knowledge. Two centuries later, over 23,000 people identify as Tasmanian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Melythina Tiakana Warrana

Like their ancestor Mannalargenna, the people of Melythina Tiakana Warrana excel at negotiating partnerships.

In 2013 it collaborated with Hydro Tasmania (now Musselroe Bay Wind Farm) to establish and jointly manage the Tebrakunna Visitor Centre at Cape Portland—the site for Mannalargenna Day each year since 2015, when it marked 170 years (to the day) since Mannalargenna's death. Since then, each year the corporation's all-volunteer staff secures small grants and sponsorship from the Tasmanian government, local councils and businesses of the north-east. Even more impressively, the Patron of Mannalargenna Day is the Governor of Tasmania. (Imagine how shocked George Arthur would be by this turnaround.)

Governor of Tasmania, Professor The Honourable Kate Warner AC, having just unveiled the memorial to Mannalargenna during Mannalargenna Day, 2016

Dancing at the 2019 celebration

Melythina Tiakana Warrana has over 200 members who trace their heritage to north-east Tasmania, and it operates with a palpable commitment to best-practice governance. Given the history, the stakes must feel high. The corporation has managed to rise above the horror. It has found a way to honour the ancestors and build goodwill between present-day Tasmanians regardless of their heritage. As founding director, Aunty Patsy Cameron, puts it:

It's just so important that non-Aboriginal Tasmanians have some understanding about present-day Tasmanian Aboriginal history and culture, and how we reconnect with our country.

In addition to Mannalargenna’s skill as a negotiator, for most Aboriginal Tasmanians today, Mannalargenna is an ancestral grandfather. So he is a powerful symbol of unity and the dynamism of Tasmanian Aboriginal cultures.

Mannalargenna Day is a testament to the astounding strength and magnanimity of Aboriginal people. We trust that Melythina Tiakana Warrana will continue to draw inspiration from Mannalargenna and all the other ancestors and past and present elders, and hope that non-Indigenous Australians continue to learn.

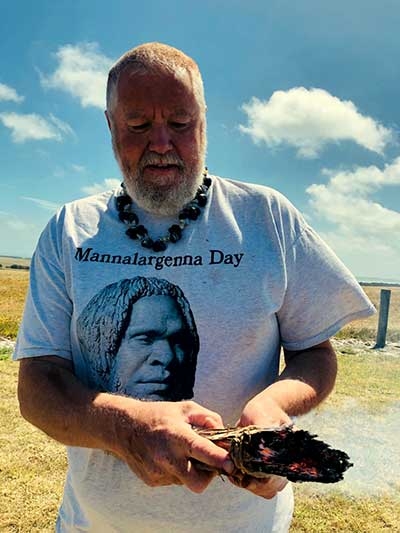

Rob Anders, director of Melythina Tiakana Warrana, has been involved in the men's circle at every Mannalargenna Day so far.

Sources

Melythina Tiakana Warrana (Heart of Country) Aboriginal Corporation and personal communication with Aunty Patsy Cameron

Mannalargenna, University of Tasmania, undated

The black line, National Museum of Australia, undated

Sally Dakis, Coming into Country—Patsy Cameron, ABC Rural, 7 July 2011

Rhiannon Shine, Aboriginal warrior: Tasmanians commemorate the anniversary of Mannalargenna’s death, ABC News, 4 December 2016

Nicholas Clements, The truth about John Batman: Melbourne’s founder and ‘murderer of the blacks’, The Conversation, 13 May 2017

Steph Harmon, Murders, massacres and the black war: Julie Gough’s horrifying journey in cultural genocide, The Guardian, 28 June 2019

Frances Vinall, Mannalargenna Day cultural celebration this weekend, The Examiner, 3 December 2019

Frances Vinall, Mannalargenna Day 2019: Tasmanian Aboriginal culture celebrated with 600 people in North-East, The Examiner, 21 December 2019